COALITIONS IN SOUTH AFRICA Bridges or barriers? Article 1 in a series of 4

It was becoming increasingly clear to me that terrible things happen when our leaders fail to think about data that are outside their typical focus.

Max Bazerman

Conflict is the sound made by the cracks in a system, the manifestation of contradictory forces coexisting in a single space.

Kenneth Cloke

Introduction, thesis and scope of the series

South African political parties have increasingly had to experiment with political coalitions in recent years, due to a variety of factors that we will consider.

Coalitions, at national and city level, are understood as being modern conflict management tools and strategies that can build bridges from current political and societal dysfunctions to improved cohesion and co-operation. But has that been South Africa’s political experience with this strategy so far?

The main thesis of this series can be set out as follows:

(i) The use of political coalitions in the South African political environment does not confer any automatic benefit to the South African electorate;

(ii)When misunderstood or misapplied, as has been the case so far, the use of coalitions do more harm than good in our national and local political conflicts;

(iii) If the harm caused by misapplication of coalitions are to be avoided, and the real benefits of political coalitions gained, sufficient numbers of our politicians, preferably on a non-partisan basis, should be trained in correctly understanding and applying these strategies at an advanced level, and for this we will need to urgently craft various aids and guardrails, such as advanced coaching and basic legislation in order to derive maximum benefit.

In the four articles in our series, I want to focus on the following main issues relating to our political conflicts and the role that coalitions play, and can play, in our political future:

1. A brief assessment of coalitions in the South African environment, seeking to understand their potential and actual role in conflicts;

2. A similar perspective on political coalitions globally, focusing inter alia on a comparative study of best practices and strategies used in specific coalitions that we can apply in the South African conflict arena;

3. Critiquing specific instances of coalitions in recent South African political history, and showing the instances of harm and poor conflict outcomes this mismanagement result in;

4. Discussing specific conflict strategies to be used in our South African coalitions, and suggesting practical ideas to realize this advice.

An attempt at defining the concept

A study of a range of political science, conflict studies and other disciplines shows a general consensus on political coalitions simply being understood as a formal or informal alliance between two or more political parties, groups or organizations, which parties then collaborate towards shared political objectives as they may view those aims. They are generally strategic partnerships where these political actors share resources and infrastructure, coordinate strategies and, in practice, seek to arrive at various compromises on policy or even ideological disputes.

In theory, these projects then create maximal influence and stability in a political environment, such as a city or province. The various powers of the involved actors, the processes involved in dealing with internal matters, the duration of the coalition and so on can be determined in advance, or as the political ice shifts from time to time.

As we will see during the course of our study, this definition should be loosely held, as coalitions in South Africa tend to be rather amorphous at times. And this is as it should be, as the involved parties should ideally be allowed to shape their own plans and processes for these ideals to be reached. If and when pending legislative developments start to guide these coalitions (see below), the definition will be tightened so as to require, for instance, coalition agreements to be recorded in writing, and dispute resolution will also be addressed more formally, at least in the Bill currently under review.

Legal frameworks

The South African Constitution, with its proportional representation framework, of course steers much of the political activities allowed to parties, and this is clarified and developed further through a well-developed body of case law and ongoing debate, at both academic and grassroots levels.

The framework is expanded by further legislative developments such as the Local Government: Municipal Structures Act (1998), the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act (2000), and the Government of National Unity’s 2024 Statement of Intent.

The chaos that ensued across our political landscape once we started to implement coalitions on a more regular and organized basis (with more than 70 hung municipalities since 2021), eventually led to the realization that some of these dysfunctionalities need to be addressed by specific legislation, and as I write this we are waiting on the enactment of the Local Government: Municipal Structures Amendment Bill (2024, B2-2025, the so-called “Coalition Bill”).

This legislation, once in effect, will require a range of common sense formalities, such as written coalition agreements, limitations to no-confidence motions, and collective executive systems that could take over from executive mayors. The public disclosure of certain aspects of coalition agreements should also ease some of the current chaos.

There are other frameworks and guides that should form part of any in-depth study or conflict work with such coalitions, such as the National Framework on Coalition, the GNU’s Medium-Term Strategic Framework and interesting discussions around electoral thresholds, designed to limit or prevent fragmentation and instability caused so often by small political parties.

I am fully in support of these frameworks and their urgent development, as they can, in this form, only be viewed as a net gain for our coalition development process. I however need to caution against too much of a complete reliance on these frameworks. They create a relatively orderly environment for politics to be conducted, and our fractious political milieu will simply not be bottled up in this manner, at least in the early years.

These legislative guides and frameworks should be studied and used completely, and with great skill and accuracy, but we are still dealing with the dynamics of human conflict, with high stakes and a web of unresolved past and current conflicts that will defeat any attempts at a complete reliance on such frameworks alone. As I hope to show with this series, the real work lies elsewhere.

Coalitions in the South African political landscape – a point of departure

The general idea of a political coalition is not that foreign to the South African political environment. It is of limited, but arguably necessary, interest to briefly look at some of these coalitions, as they may positively or negatively shape the trajectories of future South African political coalitions. These earlier coalitions, as we will see, were mostly aimed at very different operational goals than what our modern versions should be targeting.

White parties experimented with coalitions mainly to retain a hold on their non-democratic power. In 1934, for example, Jan Smuts’ United Party and JBM Hertzog’s National Party formed a coalition government. Aiming to unify Afrikaans and English whites, and to combat the economic challenges of the Great Depression, this coalition fell apart in 1939, ostensibly due to the tensions created by South Africa’s entry into World War 2. In the 1940s, the then National Party occasionally formed alliances with other minority white parties in order to reach similar categories of gain, such as the coalition with the Afrikaner party.

This tinkering with margins could again be seen in the National Party of the 1980s, when it collaborated with moderate groups and homeland leaders, from which nominal, limited reforms followed. The United Democratic Front gathered together a wide range of civic organizations, activists, religious and student organizations and others, and their work from 1983 to 1991 also shows elements of a working political coalition.

The African National Congress has a rich history of alliances with other groups and parties, some of which I believe we can include here in our early assessment of the idea in South African politics. The parties that comprised the Congress Alliance and the well-known Tripartite Alliance (ANC, SACP and COSATU) are examples of such projects that could beneficially be regarded as coalitions for our purposes.

Much of this interesting history of our political coalitions however serve more to add complexity to our current political conflicts than what it may serve as experience or lessons. Given the undemocratic environment in which so much of that took place, we are still very much struggling towards any of the working models of reconciliation, and our generally poor political leadership in recent decades have left most of our significant unresolved complex conflicts untouched.

A snapshot assessment of our current political readiness for coalitions

Coalitions, as our comparative study later in the series will show, offer an exciting and immediate conflict tool to our political and other leaders, one with which we can address so much of the current impasse and conflict rigidity that we are fighting against. However, our political landscape and heterogeneous population composition, our deeply polarized society, and our unhealed wounds of the past require a highly skilled application of coalition mechanics.

So far, in say the last decade of coalition praxis, we see precious little of such abilities or its application. Coalitions are used as battering rams, tit for tat short-term conflict strategies, and chaos and great harm ensue, with seemingly very few politicians really understanding the levers and pulleys that they have at their disposal, and for which they are responsible. In the remainder of the series we will assess specific case studies and best practices, and we will, without blinking, have a cold, hard look at our coalition dysfunctions, its causes and its remedies.

This is an inspirational and very effective conflict tool in the right hands, and a weapon of destruction in unskilled hands. In the next article in the series we do a comparative study of coalitions and their practical use in other, comparable countries.

Summary of main sources, references and suggested reading 1. Relevant articles for your general negotiation and conflict work, and their source material, can be found at www.conflict-conversations.co.za

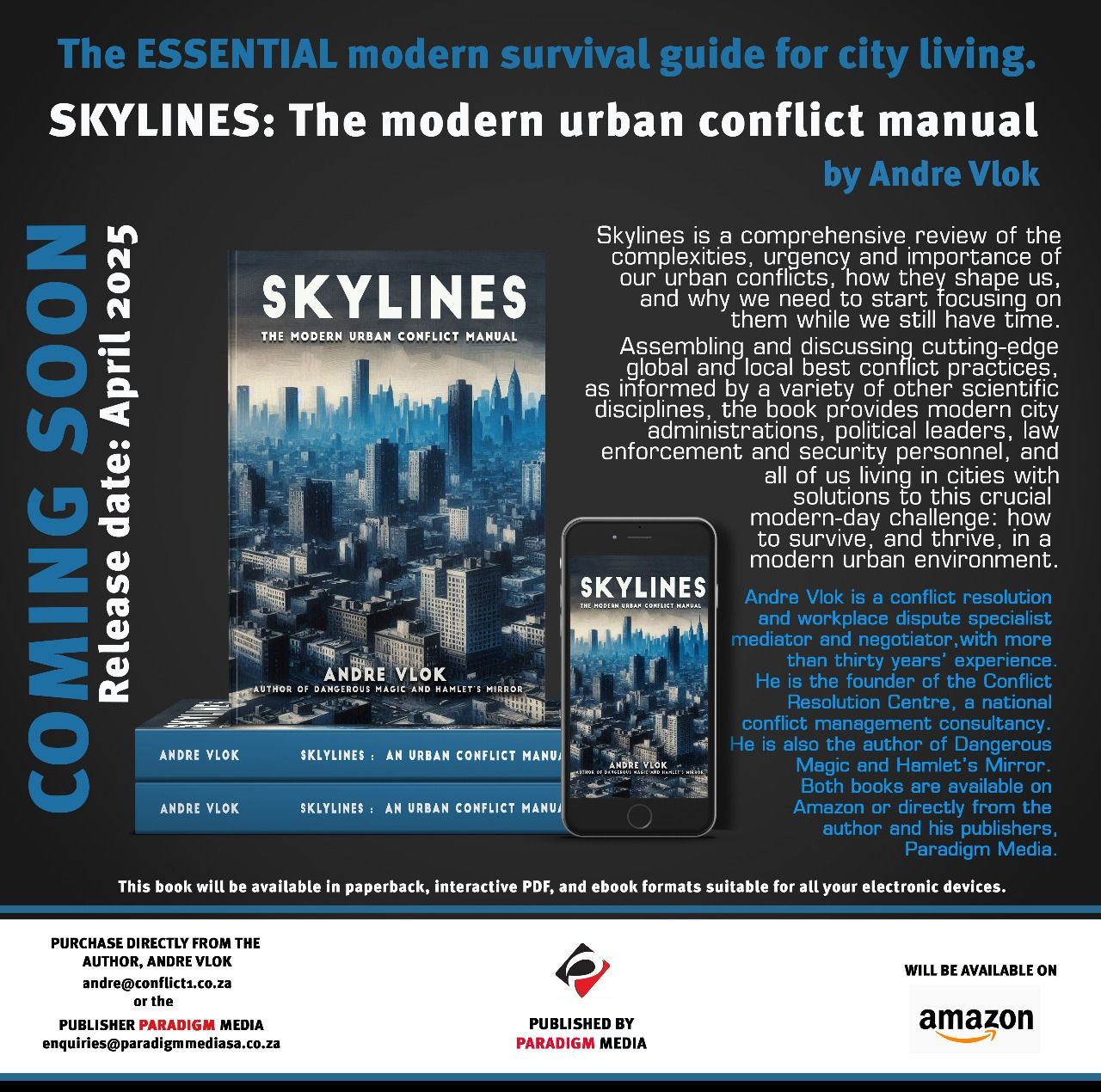

2. For an expanded argument on how our political leadership should heal the country by healing the conflict in our cities, including a discussion on modern political coalitions, see Skylines: the modern urban conflict manual, by Andre Vlok (Paradigm Media, 2025), available via Amazon or the publishers.

- Full references, further reading material, courses, coaching, study material, workshops / seminars, mediation and representation are available on request.

- A summary of Andre Vlok’s cv / bio can be accessed at https://www.conflict-conversations.co.za/conversations/2025-online-curriculum-vitae-andre-vlok

(Andre Vlok can be contacted at andre@conflict1.co.za for any further information.)

(c) Andre Vlok

September 2025